Does the Baltic Region Exist?

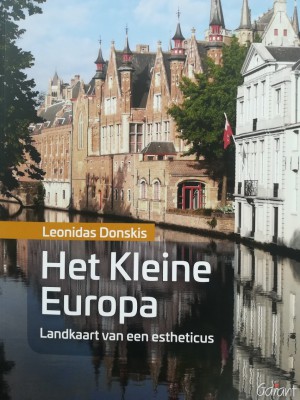

By Leonidas Donskis

What is the relationship between Lithuania and the other two Baltic nations? It differs from Latvia and Estonia in more than one way. No matter how rich in historically formed religious communities and minorities it is, Catholic Lithuania, due to its historic liaisons with Poland and other Central and East European nations, is much more of an East-Central European nation than Lutheran Latvia and Estonia. Therefore, it would be quite misleading to assume seemingly identical paths by the Baltic States to their role and place in modern history.

Lithuania’s history and its understanding would be unthinkable without taking into account such Eastern and Central European countries as Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine. Latvia is inseparable from major German and Swedish influences, and Estonia from Swedish and Danish, not to mention its close cultural ties with Finland.

Lithuania is an old polity with a strong presence in medieval and Renaissance Europe. Latvia and Estonia emerged as new political actors in the 20th century. It was with sound reason, then, that after 1990, when Lithuania and the other two Baltic nations became independent, politicians and the media started making jokes about the unity of the three Baltic sisters, which was achieved by them through their common experience of having once been three inmates in the same prison cell.

Small wonder, then, that this led Toomas Hendrik Ilves, a former foreign minister (now president) of Estonia, to describe Estonia as a Nordic country, rather than a Baltic nation. In fact, once they had come into existence, the Baltic States underwent considerable political changes in the 20th century.

It is worth recalling that Finland, before the Second World War, was considered a Baltic State too. That is to say that four Baltic States existed in interwar Europe. The fact that only three entered the 21st century is a grimace of recent history. Yet some similarities and affinities between the Baltic States are too obvious to need emphasis. All three nations stood at the same historic crossroads after the First World War. All were linked to the fate of Russia in terms of (in)dependence and emancipation. All three existed as independent states from 1918 to 1940.

At that time, all three introduced liberal minority policies, granting a sort of personal, non-territorial cultural autonomy to their large minorities, Lithuania to its Jewish, Latvia to German, and Estonia to German and Russian minorities. All three sought strength and inspiration in their ancient languages and cultures. All have a strong Romantic element in their historical memory and self-perception.

Last but not least, all benefited from emigres and their role in politics and culture. It suffices to mention that the presidents of all three Baltic States have been, or continue to be, emigres, who spent much of their lives abroad and who returned to their respective countries when they restored independence after 1990: Valdas Adamkus in Lithuania, Vaira Vike-Freiberga in Latvia, and Toomas Hendrik Ilves in Estonia. Most importantly, the trajectories of the Lithuanian and Baltic identity allow us to understand the history of the 20th century better than anything else.

Yet the questions arise: What will the Baltic Region be like in the 21st century? What will be the common denominator between Klaipeda, Riga, Tallinn, Kaliningrad, and St. Petersburg in the new epoch? Will the Baltic States come closer to the Nordic states, or will they remain a border region in which contrasting Eastern and Western European conceptions of politics and public life continue to fight it out amongst themselves?

Will we be able to apply to the Baltic countries that description by which Milan Kundera attempted to identify Central European countries: a huge variety of culture and thought in a small area? Will the tie that binds us to our neighbors be just a remembrance of common enslavement and a sense of insecurity, or will we create a new Baltic regional identity, one that is both global and open and in which we can map our past and our present according to altogether different criteria?

These are some of the questions the Baltic region raises: formulating them is no less useful and meaningful than answering them. Possibly here is where some vital experiences are tried out, experiences that larger, more influential countries have not yet had but which await them in the future.

It may be that the Baltics were and still remain a laboratory where the great challenges and tensions of modernity can be tested and the scenarios for European life in the not-too-distant future take shape.

Leonidas Donskis, Ph.D., is a Lithuanian Member of the European Parliament.

© 2010 The Baltic times. All rights reserved.